Wimbledon BookFest launches annual Young Writers Competition

Wimbledon BookFest has launched its 18th annual Young Writers Competition, with the theme of The Game.

Rose Goddard appointed Executive Director at Wimbledon BookFest

Rose Goddard, formerly Prize Manager for the Women’s Prize for Fiction and Head of Trusts at Achates, has been appointed to the newly created role.

Axis Foundation Supports Wimbledon BookFest

Donation will fund free books for schoolchildren

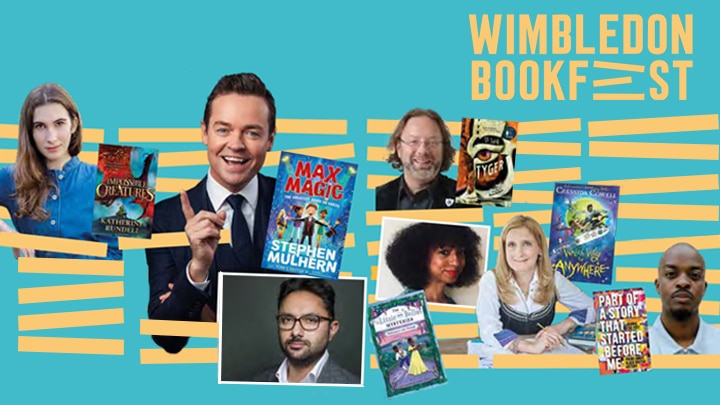

2023 – Celebrating an incredible year at Wimbledon BookFest

Packed programme of events brings the best in books, culture and the arts to south-west London

Wimbledon BookFest features in Sir Lenny Henry documentary

Sir Lenny’s World Book Day event captured on film for One of a Kind

Global Connections

Wimbledon BookFest Partners with the Lahore Literary Festival

Free tickets for Merton residents at Wimbledon BookFest

Partnership with Merton Libraries brings free events to selected postcode areas

BookFest Announces Word Up! Events For Schools

Wimbledon BookFest has announced its celebrated Word Up! programme of events for schools – welcoming some of the UK’s leading children’s authors to the New Wimbledon Theatre this autumn.

The Merton Big Read: Connecting community through books

Wimbledon BookFest – in partnership with Merton Libraries – has launched Merton’s first ever Big Read; a shared reading scheme which aims to connect the local community through books and stories.